In this text below, Lisa Ha, MSN, APRN, CNP, from Northwestern University Memorial Hospital in Chicago, Illinois, and Massey Nematollahi, RN, MScN, CNS, CON©, OCN,®, Immuno-Oncology Clinical Nurse Specialist at William Osler Health System in Ontario, Canada, discuss healthcare disparities in patients receiving checkpoint inhibitors. They provide strategies to overcome barriers to care and provide culturally competent education for immune-related adverse event (irAE) management. We hope you find this content helpful in your efforts to optimize the outcomes from immunotherapy for every patient.

Immuno-Oncology

Addressing Healthcare Disparities

Equity and Access to Checkpoint-Inhibitor Therapy

Lisa Ha, MSN, APRN, CNP

My name is Lisa Ha, and I’m a Nurse Practitioner at Northwestern Memorial Hospital in Chicago, Illinois. I’ve been practicing for about 5 years, and I specialize in melanoma and renal cell carcinoma.

Today I’m here with my colleague, Massey Nematollahi, who is also a nurse practitioner in oncology, to discuss disparities in immuno-oncology access along with the importance of cultural competency in optimizing care for patients receiving checkpoint inhibitors.

Massey Nematollahi, RN, MScN, CNS, CON©, OCN®

Thank you for the introduction, Lisa. My name is Massey Nematollahi, and I am an Immuno-Oncology Clinical Nurse Specialist at William Osler Health System in Ontario, Canada, with over 20 years experience. When I first started nursing, immuno-oncology was only being used in clinical trials. The field has made incredible advancements since then.

General Healthcare Disparities

Question from Ms Ha:

Are there healthcare disparities in oncology in general?

Answer from Ms Nematollahi:

Yes, we have found a number of disparities in cancer care. The National Cancer Society defines cancer health disparities as “adverse differences in cancer measures such as the number of new cases, number of deaths, cancer-related health complications, survivorship, and quality of life after cancer treatment, screening rates, and stage of diagnosis that may exist among groups”. [AACR 2021] It goes on to provide examples of disparities based upon geographical differences, racial differences, and socio-economic disparities.

We have noted a number of disparities ranging from disproportionate demographic group representation in clinical trials to access to treatments. The American Association of Cancer Research [AACR 2021] examined these disparities and demonstrated how a significant portion of the United States population is affected. We also have research showing disparities based on socioeconomic status, geographic location,[Sawchuk 2015] sexual orientation,[Cloyes 2018] and race.[AACR 2021]

One geographical example would be the HPV vaccination rate in adolescents. As shown in Graphic 1, those living in metropolitan areas are more likely to be vaccinated compared to adolescents living in non metropolitan areas.([Sawchuk 2015; AACR 2021] Similarly, there are differences in colorectal cancer screening favoring rural vs rural locations, and higher lung cancer incidence rates in the rural setting of Appalachia vs the rest of the United States.

Graphic 1

Racial disparities adversely affect underserved racial groups. For example, as shown in Graphic 2, we see African American men with prostate cancer having double the death rate when compared with other racial groups.[AACR 2021] African American women will have double the incidence of triple negative breast cancer when compared with white American women.[AACR 2021] As shown in Graphic 2, cancer disparities also affect Hispanic and Native American populations.

Graphic 2

Question from Ms Ha:

Would you be willing to share some personal experiences with underserved populations in your practice?

Answer from Ms Nematollahi:

I live and work in the metropolitan area of Toronto, and we see patients from all different backgrounds coming to the cancer center for their treatments. Some are patients whose self-reported income is in the lowest income bracket. Others have had difficulties finishing grade school. I find that some patients and their families are struggling to understand the cancer treatment I am explaining, causing them to become frustrated with me. Sometimes the patient will take a brochure to read at home, but I am concerned that they are not able to understand what they are reading.

A few years back, I had a very lovely and shy Vietnamese patient who had trouble understanding my English. I could tell that she was just nodding her head without understanding what I was explaining. She didn’t feel comfortable asking me any questions or confirming her treatment plan. She was more concerned with wasting my time then letting me help her.

I also remember a newly diagnosed patient sobbing as I came in the room. I offered him a glass of water with the intent of calming him down, and even in his distress, he was adamant that the water should have been room temperature with no ice. This was a strong cultural belief against chilled water. I took this opportunity to establish a relationship with the patient. And I took the time to learn and observe his culture.

These are all examples of cultural differences that may make the process of care more difficult.

I find it very important to focus only on the patient and family that are in front of me. During the initial visit, I consider their everyday challenges in life, as well as their cultural, religious, and sexual preference. It is important to build a relationship of trust with the patient and family as soon as possible, thus allowing for open communication. These are essential efforts we must make in order to succeed as a caregiver and guide to the patient and family in what can be a burdensome and weary medical journey.

Disparities in Immuno-oncology

Question from Ms Nematollahi:

What disparities are experienced by patient receiving immunotherapy?

Answer from Ms Ha:

I have found many different obstacles for patients trying to access checkpoint inhibitors.

In my experience, there are delays in treatment for patients who are under insured or uninsured. It’s difficult to navigate the current insurance system for those in the underserved community. Accessing checkpoint inhibitors through the pharmaceutical industry can be challenging and time consuming. The insurance authorization process can often place a barricade between the provider and patient. In a recent study, Tripathy and colleagues [2020] found that patients on Medicaid experience the longest delay in treatment for melanoma as compared with other insurance types, as shown in Graphic 3. There has also been a study [Li 2020] showing the difference in overall survival trends for melanoma patients post immunotherapy vs. pre immunotherapy, favoring patients with medical insurance and living in urban or low-poverty areas in the degree of improvement post-immunotherapy. The Li study also provided socio-economic analysis of patients’ age, sex, geography, economic and social factors. The study results all pointed to improved survivability if the disparities are leveled.

Sometimes patients are not able to afford the blood work and imaging needed prior to surgery and immunotherapy. We try to help these patients with financial assistance and direct them to the resources available from the drug companies. Advocacy for the patient is part of our process.

Graphic 3

I have also observed a general lack of awareness of checkpoint inhibitors in the underserved community and very rural patients. Information on the latest oncology treatments are not easily obtained by those in the lower socio-economic class.

Another struggle for the underserved population is transportation. It is a financial burden for them. Immunotherapy, as well as other cancer treatments, requires multiple office visits, and transportation to these appointments has proven to be unreliable or nonexistent. Patient treatment can be very challenging when their only option is to use public transportation.

Ms Nematollahi:

You bring up some important points. Insurance is not an issue for us in Canada since we have universal healthcare. But I have detected all the other disparities that you have spoken about. Patients traveling from very rural areas will sometimes have to stay in a hotel when having multiple days of treatment. And not all of them can afford that expense, thereby forcing them to forgo treatment. This issue is part of the unspoken problem for cancer patients.

Effects of COVID-19

Question from Ms Nematollahi:

Did COVID-19 exacerbate disparities?

Answer from Ms Ha:

Absolutely. COVID-19 affected us in so many ways as you can see in Graphic 4. At the beginning of the pandemic, we were shut down and patients started missing treatments. Only emergency surgeries were being performed, all elective surgeries were canceled. This allowed some patient’s cancer to progress, due to all services being delayed.

Graphic 4

We had to come up with ways to reach our patients. There were so many unknowns when the pandemic first started. People were scared to leave their houses and go to the clinic. Others were prevented from travel by government edict. We learned to use telemedicine with our patients. Many found that very convenient. But along with that convenience, disparities evolved. Low-income patients were not equipped with the necessary devises to make telemedicine successful. We were also incapable of examining the patient’s skin in person and/or providing certain treatments.

Social distancing impacted many communities as well. It is very common in many cultures for large multigenerational families to live under one roof. COVID-19 spread faster in those areas since social distancing was not an option for them.

Public transportation became a huge problem. I actually experienced issues myself. There was a terrible snowstorm and I was taking public transportation to work. I waited over an hour to get on the bus, while 4-5 busses passed me by with very few people on them due to mandatory social distancing. Patients would likely give up on their appointment if they had to stand in a snow storm for an hour waiting for the bus.

Countless underserved patients lost their source of income at the start of the pandemic. They struggled to make rent and buy groceries. The money they would have used to visit the physician was now going to pay for everyday living expense. For those already struggling, the pandemic brought them to a new low.

We are already seeing healthcare return back to normal with the vaccine and monoclonal antibodies now available. And hopefully we’ll see fewer delays with patients needing treatments and procedures.

Ms Nematollahi:

I remember when the pandemic first hit; the entire healthcare system was scrambling to come up with ways to continue treating patients without jeopardizing their health. We had to modify many of the regulatory protocols in a very short period of time.

We did our best.

Disparities in Clinical Trials

Question from Ms Ha:

Do these healthcare disparities also affect clinical trial enrollment? What can be done about this?

Answer from Ms Nematollahi:

Enrollment for clinical trials has always been a challenge. Having said that, there are particular disparities that do affect clinical trail enrollments. An article in the journal of Biology in Sex Differences [Klein 2020] indicates that women have always been and are still underrepresented in clinical trials.

A study in 2018 found disparities in representation by sex in clinical trials for anti-PD1 treatment.[O’Connor 2018]

Graphic 5

Since immunotherapy is a newer approach in cancer treatment, we are seeing underrepresentation of Blacks and minorities by 30% in clinical trials.[Nazha 2019; Li 2020; AACR 2021] Low accrual of minority patients in these clinical trials affects the results of efficacy due to unbalanced participation as seen in Graphic 3. Trial outcomes are missing the correct amounts of proteins, necessary biomarkers, and immunohistochemistry that vary with different genetics. Current trials are only benefiting the race that’s being studied.

Why are the different ethnic groups and minorities not enrolling in trials? As recently as an article in 2021, clinical immuno-oncology trials still fall short in enrolling racial minorities. One of the barriers in clinical trials is the source of funding. Many oncology trials are sponsored by the pharmaceutical industry, which tends to target more affluent areas for enrollment. More must be done to increase inclusion of all the underserved and ethnically varied cancer patients.

There is a nonprofit organization in the United States called CICSRP, Center for Information & Study on Clinical Research Participation. They serve the entire United States and have developed a program called Aware for All to serve marginalized communities. The program goes into the underserved communities to educate and sign patients up for clinical trials. More information about this program is in the RESOURCE LIST at the end of the document.

Unfortunately, this program does not reach Canada, and I have not found a central source of clinical trial information. It is crucial for doctors to be aware of the available trials that might benefit their patients. We have so many eligible patients for these clinical trials. But because of their social economical status, they are not being enrolled. We need to bring more education, training, and awareness to these minority groups to ensure that trial results return unbiased.

Ms Ha:

You’re absolutely right. With Congress passing the National Institute of Health Revitalization Act in 1993, which mandates the sponsored clinical trial include women and minorities, reports still show lower rates of participation in women and minorities. If you would like to peruse that act, we’ve included a link to it in the RESOURCE LIST.

I believe we can do a better job getting the clinical trials out into the communities and trying to recruit more patients to participate, so that in the future we have accurate results for all races of patients diagnosed with cancer.

Advocating for Underserved Populations at Different Levels

Question From Ms Nematollahi:

What can be done to advocate for underserved populations at the provider, healthcare system, and social policy level?

Answer from Ms Ha:

This is a complex and somewhat sensitive subject. I would like to acknowledge the work of Breanna Lathrop, DNP, MPH, FNP-BC, who is an expert in the field. One of our collaborators recently attended a presentation by Dr Lathrop at a continuing education conference.

Change needs to happen on three levels to be successful: the providers, the healthcare system, and at the policy level. See Graphic 6.

Graphic 6

This change starts with the providers. It’s important to look inward and identify any implicit biases before change can happen. Implicit bias works on the unconscious level when we encounter people belonging to specific groups. Sometimes our biases can get in the way of providing care.[FitzGerald 2017] So it’s helpful to understand what our implicit biases are and take steps to address them.

We need consider the method of health care delivery to these underserved patients.[Andermann 2016] Do they have easy access to healthcare? Is there a clinic in their community that will serve them? And does that clinic provide cross sector collaboration?

What are some steps we can take to improve access? We can begin by understanding the history and complexity from where these disparities have developed.[Van Ryn 2011] We need to understand how the social determinants of health in their community align with their pathophysiologic health [Williams 2016];WHO 2021] We need to recognize the long-term impact of living in low-income housing and lack of insurance. Providers need access to these patients’ stories and learn from their lived experience.

How can we help providers with implanting these changes? The simple answer is to provide resources within the healthcare industry.[Taylor 2016] It starts with organizational change. Due to the systemic disinvestment in lower economical neighborhoods, many clinics are under-resourced. To make changes, the clinics first need an adequate number of providers and a diverse staff. Resources must be provided for staff education, tools to implement changes, and a safe environment to report discrimination. Providers need to be given time to talk with the patient [Fenton 2011] to identify and discuss social needs during their visit.[Thornton 2016] The staff needs to be trained to recognize the individual needs of a patient, if they are being met, and identify the gaps that need to be filled.[Andermann 2018] We need to normalize talking to our patients about housing, transportation, and income. While at the clinic, we need to be able to offer the patients resources that are easily accessible. There needs to be a program in place where partners, with other areas of care—dental, food, housing, transportation—are in place and ready to use.[WHO 2021]

We need policies in place to support the providers and healthcare clinics.[LaForge 2018] These endeavors require funding and advocacy to begin changes in the healthcare system. Providers and clinics will not be able to implement any of these changes without financial assistance and support from the policy makers. The patient’s health needs to be the primary focus behind all policy changes.

Ms Nematollahi:

This is a very difficult subject to address, as it involves politics and government at the highest levels. Thank you for addressing it.

Cultural Competency and Education for irAE Management

Information on irAEs in Different Populations

Question from Ms Ha:

What do we know about irAEs in different populations?

Answer from Ms Nematollahi:

We see patients in our clinic from all over the world with varied cultures, religions, and beliefs. It is important to understand these cultures so we can communicate with the patients in ways they can comprehend. We also need to identify what keeps them from reporting side effects. For instance, some patients are economically challenged and have other life issues that take priority over their treatment. Another is fear of their treatment being terminated.

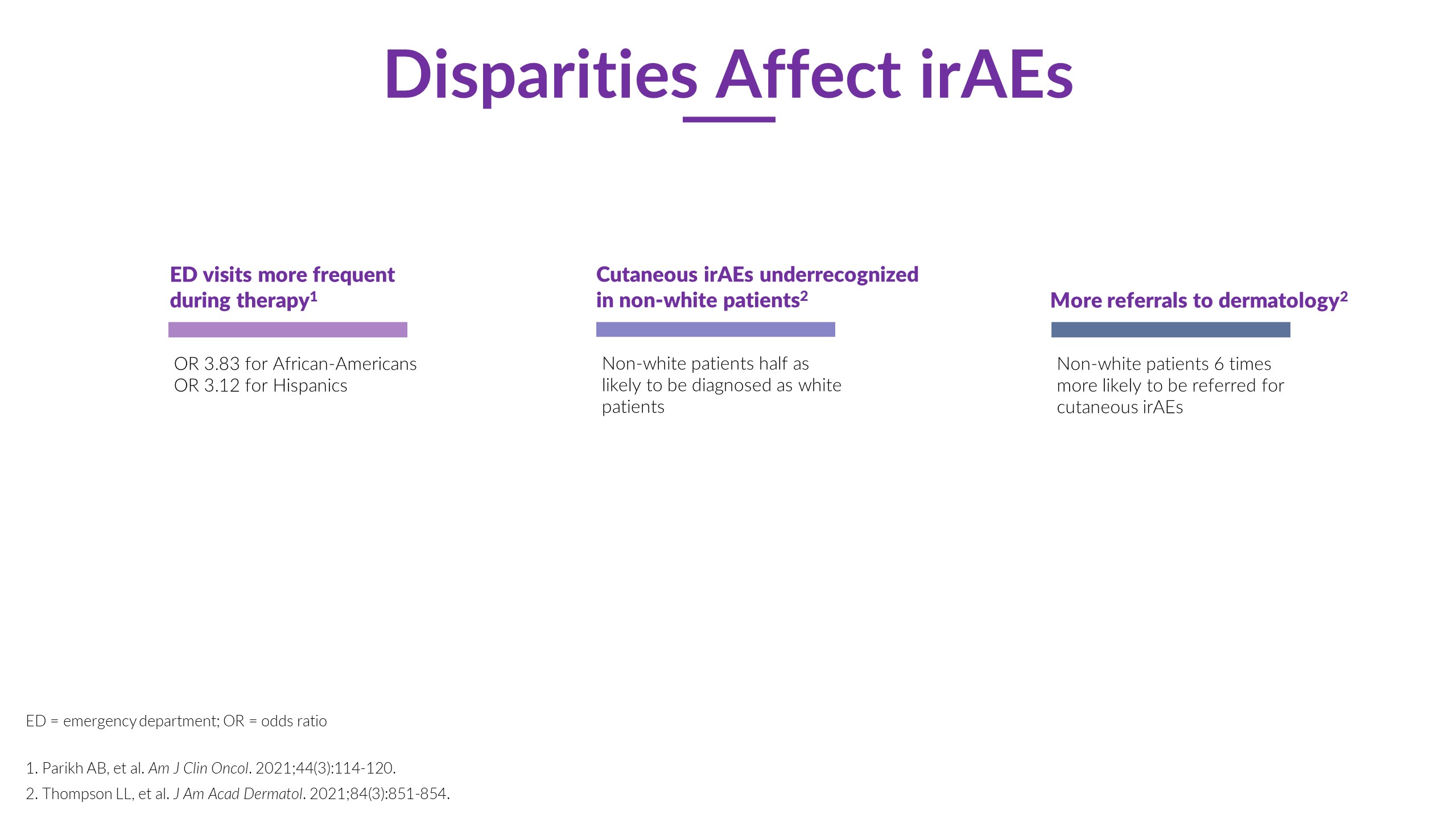

An article in the American Journal of Clinical Oncology [Parikh 2021] concluded that defining demographic and clinical risk factors for presentation to the hospital (emergency department or inpatient) for irAE management can help highlight disparities, prospectively identify high-risk patients, and inform preventive programs aimed at reducing such care. As seen in Graphic 7, the odds ratio of patients ending up in the emergency department was 3.83 for African Americans, and 3.12 for people of Hispanic ethnicity. These groups also had elevated odds of inpatient admission. Therefore, we can see that underserved populations may be more likely to have poorer outpatient control of irAEs.

Graphic 7

In the Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology, Thompson and colleagues reports that in multivariate models, non-white patients were half as likely to be diagnosed with an irAE compared to white patients. The article also found that non white patients with irAEs were 6 times more likely to be referred to a dermatology specialist than white patients. These data suggest that general practitioners need continuing education on the early signs of irAEs in IO patients so they can initiate therapy early or recognize the need for a dermatology referral.

We need to teach patients the indications of possible toxicity and explain how, for example, a rash could be the first sign of something more serious. It is also important to educate the patient on being an advocate for their treatment and not dismiss their side effects. We also need to assure them that, in most cases (particularly if caught early), they will be able to continue treatment once their irAEs are under control. Some patients avoid reporting symptoms out of fear that their treatment will be terminated.

I had a patient arrive at her appointment in a wheelchair. She was in very bad shape from an unreported irAE. The skin was peeling off the bottom of her feet in sheets, and she was in so much pain that she was unable to walk. She explained that she was willing to live in this condition if it meant she could continue treatment.

Ms Ha:

I have seen patients with irAEs, whose treatment is working, and they don’t want to interrupt the therapy. I have to help them understand that if they let the irAE get much worse, they will be admitted to the hospital, which will increase the delay in treatment or perhaps lead to permanent treatment discontinuation.

Providing Culturally Competent Education

Question from Ms Ha:

How do you provide culturally competent education to all your patients regarding immunotherapy related adverse events?

Answer from Ms Nematollahi:

Understanding the cultural differences will alter how I interact with the patients. How do I address them, what questions should I be asking of them, and what is their religious and cultural background?

To understand these differences, we need to train clinicians in multiculturalism and bring awareness to all the different ethnic groups that we serve. We need to consider their cultural differences, beliefs regarding use of herbal medicine, and lifestyle. Having a diverse clinic staff makeup also facilitates open and comfortable communication with patients.

My personal approach is to provide culturally sensitive care to my patients. Before the first appointment, the staff confirms whether the patient would prefer a nurse or doctor of the same sex or gender. During the first assessment I meet the patient in a culturally humble manner. I anticipate the cultures that do not make eye contact or shake hands. I begin by asking how the patient would like to be addressed.

Showing these cultural sensitivities will demonstrate that you care and they can trust you with their treatment. Once the trust has been built, you can then education them on the importance of reporting irAEs.

Ways to Encourage irAE Reporting

Question from Ms Ha:

What are some ways you encourage your patients to report irAEs?

Answer from Ms Nematollahi:

After establishing trust with my patients, I begin to educate them on the importance of reporting all adverse reactions as soon as possible. I encourage them to call us and report every reaction and assure them no symptom is too small. I overemphasize that we don’t consider it to be a bother when they call our clinic.

It is very important to have a discussion with your patient about home remedies and herbal supplements. Some cultures have very strong beliefs in their ability to cure them. I had a patient from India who was doing very well with his immunotherapy. He believed it was because of his daily consumption of turmeric and not his treatments. He would not be convinced otherwise. Another patient accidently dropped a mushroom from her pocket that she had purchased from her country. I tried to convince her that it was not safe to use with her treatment. She argued with me and explained how it had cost her a lot of money. She believed that these mushrooms were curing her cancer.

While respecting patients’ culture, we need to educate them on possible side effects of herbal supplements while on immunotherapy and the contraindications they could cause.

Clinicians must be trained to recognize unconscious implicit bias and be open to change. The first interaction between patient and staff will determine whether the patient calls again with another side effect. Providing the staff with education on how they should respond will greatly benefit the patient. The staff must be mindful to not underplay the reported side effects. There is beneficial knowledge in understanding the cultural difference in how patients present themselves. We must be aware that some cultures and generations are much more reserved and subtle when they speak, just as some are loud and exaggerated. We must give equal validity to all patient reports.

Our center, in collaborating with the Society of immunotherapy in Cancer (SITC), has created educational videos about immunotherapy treatment. In them we go over the differences between immunotherapy and chemotherapy. We also have provided the information in nine of the most common languages in our area. See links to these tools in the RESOURCE LIST.

In general, I’m there for the patient, I listen when they speak, and let them know that they have my support. By establishing a trusted relationship, they feel safe and clearly communicate and report any possible irAEs.

Ms Ha:

I agree that a lot of these cultures rely on herbal medicine as a form of treatment. Coming from an Asian culture myself, I see how my parents and grandparents believe in these herbal supplements. With immunotherapy being somewhat new, we do not currently have a lot of data on how immunotherapy interacts with herbal medications. But I have seen how the medications affect the treatment itself. We had a patient who had developed hepatitis as a side effect. When we asked him to stop his herbal supplements, the liver magically began to function as normal again. It is very difficult to convince these patients that some herbal supplements are causing harm instead of helping.

I advise all my new patients to report side effects as early as possible. I emphasize that this in turn will help them continue their treatment safely. I constantly remind my patients not to feel like they are bothering us with what may seem to be minor reactions. We want to know if they are experiencing any side effects, even if it’s one episode of diarrhea. Many cultures are worried about becoming a bother, and our job is to assure them that in fact we want them to bother us. We keep emphasizing during every visit that we want them to call for everything. I think with that kind of encouragement, along with building a solid relationship, we are successful in eliciting early reporting of side effects.

Reference List

AACR, Cancer Health Disparities. Accessed from https://www.aacr.org/patients-caregivers/about-cancer/cancer-health-disparities/ on October 6, 2021.

Andermann A. Taking action on the social determinants of health in clinical practice: a framework for health professionals. CMAJ. 2016;188(17-18):E474-E483. doi:10.1503/cmaj.160177

Andermann A. Screening for social determinants of health in clinical care: moving from the margins to the mainstream. Public Health Rev. 2018;39:19. doi:10.1186/s40985-018-0094-7

Cloyes KG, Hull W, Davis A. Palliative and End-of-Life Care for Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, and Transgender (LGBT) Cancer Patients and Their Caregivers. Semin Oncol Nurs. 2018;34(1):60-71. doi:10.1016/j.soncn.2017.12.003

Fenton, Health Care’s Blind Side. Accessed from https://www.rwjf.org/en/library/research/2011/12/health-care-s-blind-side.html on February 2, 2022

FitzGerald C, Hurst S. Implicit bias in healthcare professionals: a systematic review. BMC Med Ethics. 2017;18(1):19. doi:10.1186/s12910-017-0179-8

Klein SL, Morgan R. The impact of sex and gender on immunotherapy outcomes. Biol Sex Differ. 2020;11(1):24. doi:10.1186/s13293-020-00301-y

LaForge K, Gold R, Cottrell E, et al. How 6 Organizations Developed Tools and Processes for Social Determinants of Health Screening in Primary Care: An Overview. J Ambul Care Manage. 2018;41(1):2-14. doi:10.1097/JAC.0000000000000221

Li D, Duan H, Jiang P, et al. Trend and socioeconomic disparities in survival outcome of metastatic melanoma after approval of immune checkpoint inhibitors: a population-based study. Am J Transl Res. 2020;12(7):3767-3779.

Nazha B, Mishra M, Pentz R, Owonikoko TK. Enrollment of Racial Minorities in Clinical Trials: Old Problem Assumes New Urgency in the Age of Immunotherapy. Am Soc Clin Oncol Educ Book. 2019;39:3-10. doi:10.1200/EDBK_100021

O’Connor JM, Seidl-Rathkopf K, Torres AZ, et al. Disparities in the Use of Programmed Death 1 Immune Checkpoint Inhibitors. Oncologist. 2018;23(11):1388-1390. doi:10.1634/theoncologist.2017-0673

Parikh AB, Zhong X, Mellgard G, et al. Risk Factors for Emergency Room and Hospital Care Among Patients With Solid Tumors on Immune Checkpoint Inhibitor Therapy. Am J Clin Oncol. 2021;44(3):114-120. doi:10.1097/COC.0000000000000793

Sawchuk CN, Van Dyke E, Omidpanah A, Russo JE, Tsosie U, Buchwald D. Caregiving among American Indians and Alaska Natives with cancer. Support Care Cancer. 2015;23(6):1607-1614. doi:10.1007/s00520-014-2512-9

Taylor LA, Tan AX, Coyle CE, et al. Leveraging the Social Determinants of Health: What Works?. PLoS One. 2016;11(8):e0160217. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0160217

Thompson LL, Pan CX, Chang MS, Krasnow NA, Blum AE, Chen ST. Impact of ethnicity on the diagnosis and management of cutaneous toxicities from immune checkpoint inhibitors. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2021;84(3):851-854. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2020.09.096

Thornton R, Glover C, Cene C, Glik D, et al. Evaluating strategies for reducing health disparities by addressing the social determinants of health. Health Aff (Millwood), 35(8):1416-23. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2015.1357

Tripathi R, Archibald LK, Mazmudar RS, et al. Racial differences in time to treatment for melanoma. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2020;83(3):854-859. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2020.03.094

van Ryn M, Burgess DJ, Dovidio JF, et al. The impact of racism on clinician cognition, behavior, and clinical decision making. Du Bois Rev. 2011;8(1):199-218. doi:10.1017/S1742058X11000191

WHO, Social determinants of health. Accessed from https://www.who.int/health-topics/social-determinants-of-health#tab=tab_1 on February 2, 2022

Williams DR, Priest N, Anderson NB. Understanding associations among race, socioeconomic status, and health: Patterns and prospects. Health Psychol. 2016;35(4):407-411. doi:10.1037/hea0000242

Resource List

- American Academy of Family Physicians, AAFP, Social Needs Screening Tool: https://www.aafp.org/dam/AAFP/documents/patient_care/everyone_project/hops19-physician-form-sdoh.pdf

- Aware for All: https://www.ciscrp.org/events/aware-for-all/

- Center for Information & Study on Clinical Research Participation (CISCRP): https://www.ciscrp.org/

- Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS), The Accountable Health Communities Health-Related Social Needs Screening Tool: https://innovation.cms.gov/files/worksheets/ahcm-screeningtool.pdf

- Health Leads Screening Toolkit: https://healthleadsusa.org/resources/the-health-leads-screening-toolkit/

- National Association of Community Health Centers, PRAPARE assessment tool: http://www.nachc.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/05/PRAPARE_One_Pager_Sept_2016.pdf

- NIH Policy and Guidelines on The Inclusion of Women and Minorities as Subjects in Clinical Research https://grants.nih.gov/policy/inclusion/women-and-minorities.htm

- SITC connectED Patient Resources: https://www.sitcancer.org/connectedold/p/patient

- William Osler Health System: What is Immunotherapy? https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=-93MlDl2B0c